How Does a Posek Come up with His Pesak?

From Halachipedia

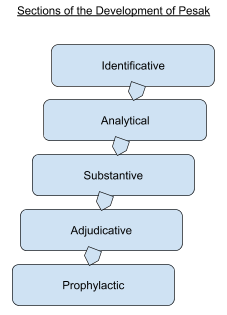

Development of Pesak

Rabbi Dr. J. David Bleich organized the halachic system into five sections:

- Substantive: The substantive part of halacha is learning a halachic sugya to the halachic conclusions. For example, if there is an opinion that the gemara rejects, the halacha doesn't follow that opinion. If there is a dispute between Abaye and Rava, the general rule is that we follow Rava. Alternatively, if the gemara leaves a matter unresolved, depending on the weight of the matter a certain halachic conclusion is drawn. These can be found on the Klalei HaGemara page.

- Identificative: The identificative section involves issue spotting and breaking up the question into its component issues. Every question can be resolved into one or several halachic quandaries and each needs to be dealt with separately and then put together. When there is a clash that too needs to be addressed; part of that topic could be found on Which Mitzvot Take Precedence? page.

- Analytical: The analytical area of halacha is to analysis the deeper logical underpinnings of the halacha in question. Sometimes it is critical to properly understand the precise nature of that halacha in order to apply and expand its details accurately.

- Adjudicative: The adjudicative role in halacha is to apply the axioms of halacha’s (halacha k’batray, rov and mechadedei, safek deoritta) when there are different claims as to what the halacha is. The canons of time periods in Torah literature involves mesorah (tradition and precedent) and minhag. These canons are discussed on the Klalei HaPoskim and Klalei Halacha pages. As noted in the vast pages in the Klalei HaPoskim category many different poskim have different sets of rules and styles that they follow in rendering a decision.

- Prophylactic: The prophylactic aspect of pesak is relevant when the rabbi can advise the one asking the question as to how to avoid the halachic quandary. Sometimes it isn't necessary to get involved with all of the complexities and opinions, if the rabbi can cleverly steer clear of the issues at hand. Furthermore, prevention of questions is also upon the rabbi with foresight to advise someone in order not to get into a question to begin with.

Character Prerequisites

Humility

- Several sources indicate that it is critical for someone engaged in the halacha to have humility in order to discern the correct halacha.

- Avot 1:1 tells us that Moshe needed to learn the lesson of Har Sinai, the smallest of the mountains, in order to receive the Torah.

- Rashi Vayikra 10:20 writes that Moshe was not embarrassed to declare that he made a mistake. That is the mark of a posek with true integrity. This idea is also found in Zevachim 100a.

- Ritva Eruvin 13a explains that the halacha follows the opinion of Bet Hillel since they are humble since it is more likely that a humble person will reach the truth. Someone with arrogance isn't interested to hear or understand the other opinion. One who is truly humble is likely to consider all the possibilities suggested before coming to a conclusion.

Yirat Hashem

- In order to have the keys to understand Torah and halacha, a prerequisite is Yirat Shamayim.

- Shabbat 31a establishes that for all of the wealth of Torah a person could amass none of it is as consequential without Yirat Shamayim. Yirat Shamayim is compared to the storage house in which the grain can be kept safely; so too Torah is only granted to those with Yirat Shamayim. The same idea is found in Brachot 55a and Nefesh Hachaim Shaar 4 elaborates on this point.

Lishma

- A person who is trying to discern the halacha must be objective and focused on finding the truth in Torah.

- Shiltei Giborim Shabbat ch. 2 writes that someone who is truly set on finding the halacha with no ulterior motives will be able to derive the correct halacha with Hashem's help even if they don't have the intellectual capabilities that are generally necessary.

- The Ramban (Introduction to Milchamot Hashem s.v. vata) writes that there are few impeccable answers that force someone to have to agree to a certain halachic conclusion. It isn't a science which requires absolute proofs. However, there are powerful arguments that are mustered to show which approach is most reasonable based on the primary evidence. A person must focus his strength and mental capabilities in order to endeavor to understand the truth.

Based on Precedent or Intellect

Precedent

- Horiyot 14a discusses whether it is preferable to hire a Rosh Yeshiva who is knowledge and memorized the primary texts or an expert in the field of Talmudic logical deducations. The Gemara rules in favor of the one who is knowledgable in the primary texts.

- Ri Migash 114 considers whether a rabbi who knows how to study the Talmud and is intellectually capable or one who isn't knowledgeable of the Talmud or its interpretations but does know the rulings of the Geonim on halachic matters is more fit to be a posek. He clearly posits that the one who knows the rulings of the Geonim is the better candidate since it is generally difficult to find anyone capable of deducing the halacha on his own from the Talmud. One who follows the Geonim even without knowing their proof is relying upon the prestigious Bet Din whose rulings are accepted.

Need for Understanding

- Rosh responsa 31:9 writes that anyone who rules based on the Rambam without knowing on what it is based on will make mistakes in halacha because the Rambam includes no reasonings. The reader can fool himself in thinking he understood even though he didn’t. You can’t pasken based on the Rambam without seeing a proof for it from the gemara.

- Sefer Haeshkol (Hilchot Sefer Torah p. 50) tells of the time someone asked Rav Paltay Goan whether it is better to study halacha in depth or to study short quick halachot. He answered that it is a terrible thing to only study the shortened versions of halacha since they minimize the torah and furthermore, they cause torah to be forgotten. They were only established to review torah and if you are unsure about something in gemara, you can use them as an aid.

- Maharsha Sotah 22a comments on the statement of chazal that those who rule based on the mishna are destroyers of the world. In our generation, those who rule from Shulchan Aruch without understanding the topic, analyzing it from the gemara, he’ll err in halachic rules and is included in the destroyers of the world. He should be rebuked.

Nuances in Halacha

- Kesot (Introduction) writes that Torah study and its analysis in an enthralling actvity. He cites the Ran (Drashot 11) who says that even if in theory the rabbis came to a conclusion that is objectively incorrect, those who follow it will recieve the same reward as if the rabbis came to the correct conclusion. Even though and its rewards are objective, the mitzvah to follow the rabbis is of such importance it grants life to its adherents. The Kesot notes that this is the interpretation of the words "חיי עולם נטע בתוכנו" - "a perpetual life you have given us" to refer to Torah study that can generate life. With halachic analysis in the proper method and mindset the results are spiritually significant to give life in the world to come and reward to its observers. He ends that a sign that a person is learning correctly is that he is finding that his intuition is in harmony with the rishonim.

- Chazon Ish (Pear Hadur v. 4 p. 186) once responded to a complaint that his idea wasn't found in Shulchan Aruch that if someone correctly has a nuance in halacha it isn't an issue that it isn't found in the Shulchan Aruch. If that was our attitude we'd never learn anything.

Disagreement with Rishonim

- Chut Meshulash (responsa siman 9) of Rav Chaim Volozhin quotes the Gra as saying that a person should be careful not to favor the earlier poskim and instead he should rule in accordance with whoever seems to right. Rav Hershel Schachter ("How to Pasken Shailos" min 28) said that the Gra would use this rule even to rule against Shulchan Aruch but we can't apply this today since we're not as great experts as the Gra was.

- Rabbi Aharon Feldman (Eye of the Storm p. 4) wrote in an attack on Feminist Halacha that "It is a fundamental principle–although often unknown or ignored–in determining Jewish law that halachah is determined by the cumulative decisions of generations of commentaries and decisors. Thus, an opinion of the Rishonim, when codified by the major later authorities, is inviolable. Rav Aharon Lichtenstein in his review of Rabbi Felman's book (Jewish Action Spring 2010) wrote "Dominant? Certainly. But flatly and categorically definitive? A question to be asked. I vividly recall hearing the summary of mori verabbi, Rabbi Aharon Soloveitchik, zt”l, of this issue’s parallel controversy between the Ba’al Hama’oer and the Rabad, as to whether Rishonim could disagree with Geonim: “If one has broad shoulders, he can contravene Rishonim. The Sha’agas Aryeh disagreed with Rishonim in many places.” Of course, the prerogative of challenge, if it exists, is not fully or routinely available to all, and is reserved for subsequent halachic leadership. In practice, it is therefore of miniscule application..."

Intellectual Honesty

- Rabbi Hillel Goldberg (Jewish Action Winter 2011) regarding the ensuing letters between Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, Rabbi Michael Broyde, and Rabbi Yosef Weiner he writes "The stakes here are broad: not only the fundamental method of Rav Moshe Feinstein, but of other first-rank posekim, too. The issue is the definition of intellectual honesty within halalchic decision-making... the correct interpretation of even one single word in a sophisticated rabbinic responsum can make a critical difference." Rav Moshe Feinstein's statement in Igrot Moshe YD 1:101 is translated by Broyde as “But in cases of great need... we are certainly obligated to rule [leniently], even if we merely deem it plausible to be lenient [my emphasis], and it is forbidden for us to be among the humble....” However, Rabbi Weiner with the additions of Rabbi Goldberg more precisely translates it as "But in cases of great need... we are certainly obligated to rule [leniently], even if the full force of my polymathic halachic knowledge yields a lenient ruling here because it is compelled by the sources..."

Sephardic Style

- Yabia Omer (v. 1 Introduction) writes that it is better to rely upon the rishonim than deducing our own conclusions from our analysis of the gemara. What could we know that they didn't? We shouldn't be so arrogant to disregard their opinion unless there is a clear proof and all the great contemporary rabbis agree, which is exceedingly unlikely.

- Ben Ish Chai (Rav Poalim Introduction) notes that even an established rabbi should look into the contemporary sefarim, those who have innovated on their own and who who has collected ideas from before them. Maybe through those readings you’ll find something new like Rabbi Yochanan listened to his student questions. This was the way of the sephardic rabbi to search the achronim and the contemporary sefarim to distill the halacha.

Ashkenazic Style

- Igrot Moshe (v. 1 Introduction) boldly pronounced that once the truth is clarified according to the view of the rabbi, after he put a lot of effort to learn and analyze the halacha from the gemara and poskim, he should then pasken in accordance with his understanding. That is his obligation and even in this generation we can consider rabbis to be capable of giving a pesak that would arrive at the truth.

- Rav Schachter (Nefesh Harav p. 19 and p. 24) describes how one theme in brisker pesak is be concerned for all the opinions. Minhagim are part of the broader scope of torah, not just for how we follow them but also in how they are established. Any minhag which isn’t based on some version of the gemara or rishonim or has logical basis in halacha is a mistake.